Why has the winter been so warm, and will it end cold? UPDATED

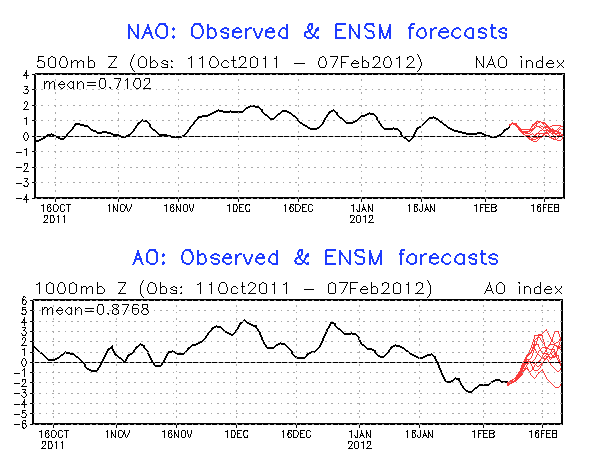

I have updated this blog with pictures sent to me by Troy and Jen Gibbons, who have a friend serving in Siberia. The blog discusses how, until the last couple of weeks, the cold air had been bottled up in the Arctic. Things are changing now though, as the AO is negative and the NAO is headed down.

This blog will attempt to explain, in fairly plain language, some of the material on atmospheric dynamics that I have taught in graduate courses at UAH. However, I think weather enthusiasts, and even those who just want to know the forecast, will get something out of it.

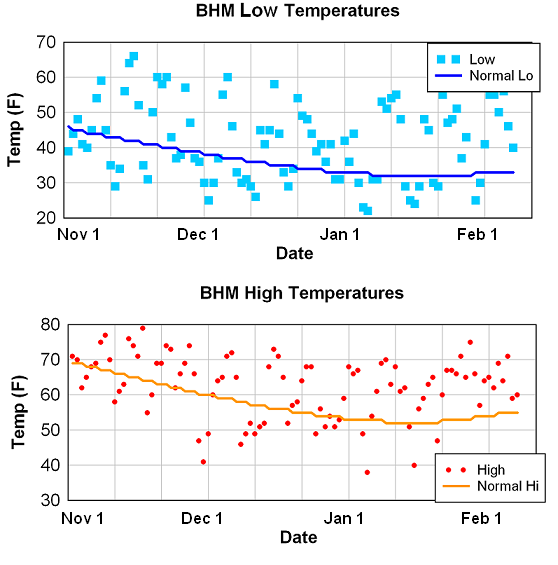

It has clearly been a warm winter so far in Alabama, and actually over the eastern half of the US. By my calculations (using data from Alabama state climatologist John Christy’s website), looking back at winters (Nov-Mar) since 1897, we’ve had the 21st warmest December, the 15th warmest January, and overall, if temperatures stay on the current track, we’ll have the 12th warmest winter on record. Normally, for Nov 1 through Feb 6, the average temperature at BHM is 46.9. Since Nov 1 2011, it has been 52.2, or 5.3 degrees above normal. That’s a lot for a 3+ month period.

Normally in an average late fall/winter/early spring, we have 52 nights at or below freezing in BHM. So far this year, we have only had 25.

1. The general atmospheric circulation, maintaining balance, and how we get our cold air

To begin the discussion of all this, I will start with the basic, large-scale dynamics of the atmosphere over the Northern Hemisphere. There is a lot more sun energy warming the earth in the tropics than in the arctic, and the difference is much larger in winter (they get practically no sun energy at all in the Arctic in winter). If there were no weather systems to balance things out, temperatures would drop to -100 F or lower in the Arctic, and stay in the 70s or so in places like Alabama all winter.

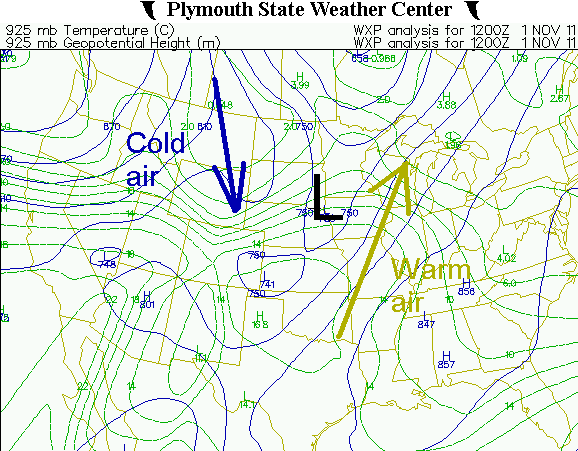

But, we do have weather systems, in the form of areas of surface low pressure, associated cold fronts, and upper-level troughs and ridges. When a low pressure area forms and intensifies along a cold front (lows tend to stay near fronts most of the time), a counterclockwise flow develops around it. As shown in the example below (solid blue lines represent pressure, and dashed green lines are temperature), this pushes warm air north and brings cold air south.

These systems are part of the general circulation of the atmosphere, that redistributes heat northward from the tropics to the Arctic, and angular momentum and other stuff. The cold air is generally associated with upper-level troughs (since it is more dense and pressure changes rapidly with height in cold air), and warm air is associated with upper-level ridges. The atmosphere has to develop these low pressure areas and associated upper waves (called Rossby waves) to maintain balance.

Below is a computer model from Naval Research Lab showing a simplified Northerm Hemisphere, with the north pole in the middle, that is coldest in the middle (temperature on the right), and what happens when that unstable situation is present. Lows and highs (left) form and redistribute the heat north and cold south.

Some winters, the atmosphere is more efficient in moving cold air south and movjng warm air north. One way to explain the overall northern hemispheric weather pattern is through the Arctic Oscillation (AO). When the extremely cold air stays bottled up in the Arctic regions (Alaska, northern Canada, Siberia), and does not get flushed out very often into midlatitudes (US, Europe, Asia) by cold fronts and low pressure, it causes the surface pressures to be high in the Arctic relative to the midlatitudes (since colder air is heavier and often causes higher pressure). This is a positive AO. When the cold Arctic air frequently gets pushed southward into the US/Europe, pressures are higher here and lower in the Arctic…this is a negative AO.

The past two winters (2009-10 when it dropped into the teens so many times and the edges of the Warrior River froze, and 2010-11 when we had several snow storms) were very negative AO…the cold air got moved out of the Arctic often, making us cold but the Arctic warmer than normal.

2. Why has it been so mild this winter?

A similar indicator (and one James points out a lot on the blog) is the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). It measures a pressure difference, but only over the North Atlantic (comparing Iceland to Portugal/The Azores). A positive NAO is generally connected with a strong jet stream over the north Atlantic, and southwesterly upper flow over the eastern US that keeps Arctic air from being able to come south.

This year the NAO has been positive so far, so cold air can’t come south as easy over the eastern US and it doesn’t stay as long. The AO, representing the northern hemisphere, was also positive until late January. This means the cold air has stayed in the Arctic (it has been -20 to -60 degrees F over a large area this winter in the Arctic, abnormal for them, and there is debate about a possible record US low temperature, see https://www.alabamawx.com/?p=56957. But, the AO has gone negative. This is associated with bitterly cold air over Europe.

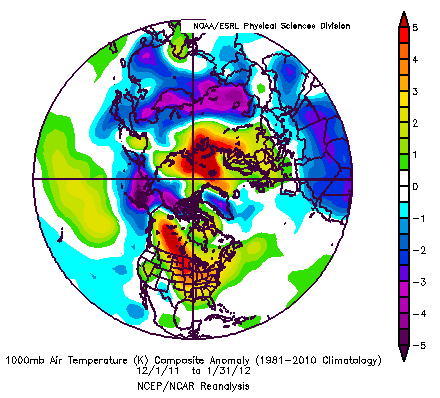

The map below shows the temperature anomaly (difference from normal) for December 1 through January 31. Note the abnormally cold air in Alaska and Siberia, and the abnormally warm air from western Canada down into the eastern US.

3. How about the rest of the winter?

This is hard to say. As James and I discussed early this week, with cold air moving into Europe the hemispheric pattern is changing, and perhaps this could kick the NAO to negative later in Feb or Mar, etc. The large scale upper-level waves have a lot to do with how all this plays out, but at least things are shifting now. What happens in the Pacific (El Nino/La Nina), what happens in Europe, etc. all can have an effect on our weather here over a longer period of time.

We are already back to near normal temperatures for early February now, and the models do indicate several pushes of cold air coming south over the next 2 weeks. But, as we get later into the winter, the sun is getting stronger over Alabama, so it makes long-term cold like we had the past two years much more unlikely. This is not to say it won’t get bitterly cold before the winter is over. A sudden pattern change in late February or early March could still get us down into the teens, and remember the Blizzard of 1993 was on March 13.

OK, here are the pictures from Siberia. Temperatures there -30 to -50 have been common this winter. That road must have buckled or something due to extreme cold/ice expansion?

Category: Alabama's Weather